If Moscow, with its punk and skater subcultures, is the next fashion destination, then Gosha Rubchinskiy is its poster boy. The Russian designer is not a household name, but that’s hardly surprising. His clothes are tricky, esoteric even: gently oversized utility jackets, high-waist jeans tied with shoelaces; T-shirts emblazoned with the hammer and sickle. Along with Georgian/Parisian label Vetements, he is the hottest designer in menswear; his collections routinely sell out and today, during the interview, there are actual autograph collectors behind us.

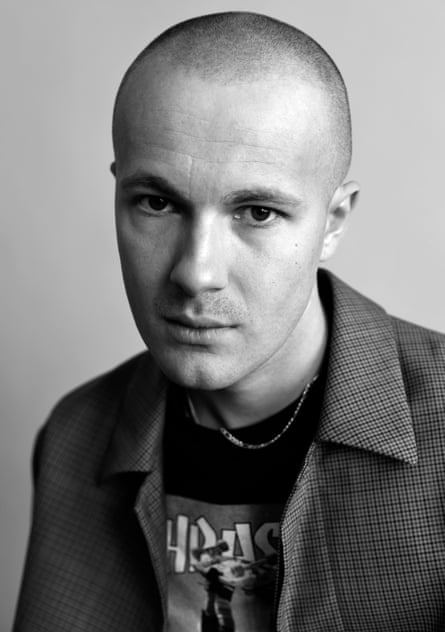

Rubchinskiy, like his clothes, is a slave to nostalgia and still styles himself like a 1990s Muscovite. Short, slim with a shaved head, loose jeans and sweatshirt, he looks like the skateboarders he hung around with in Moscow in that decade after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Across his sweater is the Gosha logo – Гоша Рубчинский, his name in Cyrillic – written in a prosaic font, which has become fashion’s emblem for disenfranchised youth, a group that defines itself by its rejection of consumerism. Last autumn, his line of red T-shirts with hammer and sickle logos, which sold out almost instantly, were another example of what he is trying to do: subvert the space between catwalk and streetwear. The people who wear them are young, too young, in fact, to understand what the symbol means, but this doesn’t matter to Rubchinskiy. “In Ukraine last year we noticed kids buying clothes with the symbol thinking it was a fashion thing – it’s almost lost its meaning,” he says. “So using it, it’s not that we believe in it, but that we are referencing what is going on in the world.”

His latest move is a unisex perfume, and, at the launch in Dover Street Market in London, his fans are exactly as he describes: teenage boys, “Gosha-heads”, who look and dress like the designer. Shaved heads. White tees. Pocket money in their palms. In high-fashion currency, his stuff is affordable (£20 for socks, less than £100 for T-shirts) which is important to him, “to make it more accessible to kids who are like me”.

Rubchinskiy, 32, was born in Moscow in 1984, and was in his first year at school when the USSR collapsed: “I was six, so I saw the last Soviet moments and the early Putin era.” He remembers the army shooting the government building, tanks rolling through the squares. But the biggest impact on this “quiet boy” who spent most of his time drawing, was what came after the collapse: fashion and culture, dancing in front of his TV to PartyZone, “which was like being in a club”, and zeitgeisty publications such as Ptyuch and OM, which laid down the blueprint for Russian lifestyle, music and culture in the way that the Face had done in Britain. “I am a product of these magazines. We all are.”

“We” refers to his friends, a primordial generation of “eastern bloc” fashion types including Demna Gvsalia of Vetements and Lotta Volkova, the cult stylist. They come from Georgia and Vladivostok, respectively, and are all roughly the same age. The three met through Lotta, partied in Paris, and model in each other’s shows: Rubchinskiy opened the Vetements SS16 show in the infamous DHL T-shirt; Lotta styles both designers’ shows; and both have the capacity and power to fly in skater friends from Russia and Georgia to model. As a result their shows stand out as being decidedly unglam and street-focused. Katerina Zolototrubova, fashion editor of Russian Vogue, describes this look as “Gopnik”, a problematic term used to describe “the bad boys from suburbs” in Russia, and aesthetically not dissimilar to what is happening in the UK, with designers such as Caitlin Price and Cottweiller. Rubchinskiy’s pieces sit in the same frame, except with the skater twist (“one of the last subcultures we have”), wistfully referring back to the stuff they were wearing in the 1990s, including Tommy Hilfiger, Adidas and Nike. “Everything was branded with logos. It was the first time we’d had that. I’m looking back at that.” These are 1990s “kids” riffing on the nostalgic post-Soviet fashion of the Russian free market. Which, in short, is the very definition of cool at the moment.

It also mirrors the challenge youth faced before the collapse: how to be culturally engaged when commercial fashion was unavailable: “We knew about it, the brands, the logos – we just couldn’t get it”. Though Gosha wouldn’t define himself as a communist, or talk directly about Putin, he thinks there is some good in most ideologies and, regarding communism, he speaks of “the freedom and what it brought”. Equally, though, his interest is in reflecting what is having a referential moment in fashion – “although I’d say it’s more like Marxism and socialism. It’s all on the table.”

And it’s true. In the west, there has been a resurgence in youth engagement with leftwing ideologies. This, as in Russia, can be seen as a response to the excesses of capitalism, Putin’s Russia and the rise of inequality. What could be cleverer than to brand the nostalgia people feel for the Soviet Union, to take a memory of communism and put it into the capitalist sphere? The hammer and sickle has a clear definition but to this new generation, it has lost some of its historical and political context. Rubchinskiy is referencing the punk bands that used it when he was growing up. “It’s also a bit of humour. I want to provoke people,” he says, smiling as a Gosha-head comes over for an autuograph. Rubchinskiy patiently signs. He wants to nip out to stock up on Lonsdale T-shirts, though – “another brand we couldn’t get in Russia” – and, with that, heads off to Lillywhites.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion