On September 5, 2006, Facebook—then two years old, far from an IPO, and still sometimes known as The Facebook—introduced what would become its defining feature: the news feed. Where once users scrutinized their friends’ profiles for changes in music taste or relationship status, now these life events found you.

“John added ’30 Rock’ to his favorite TV shows.”

“Monica is now single.”

About 12 million people, largely American college students, were using Facebook at the time, and the news feed was not what they had signed up for. Many revolted, their protestations spreading easily—and, yes, ironically—thanks to the new stream of updates on Facebook’s homepage. “Alice joined the group Dear Zuckerberg, I Disapprove of Your Changes to Facebook, Signed EVERYONE” was a typical story filling up news feeds back then.

“I’m friends with 200 random assholes from Harvard,” a friend emailed me on the morning that Facebook unveiled the news feed. “I don’t need them getting a notice on their login page every time I post a photo of you and me smoking a joint, or an innuendo on Sarah’s wall.”

Facebook, which would eventually secure a patent for “Dynamically providing a news feed about a user of a social network,” portrayed the feature as both revolutionary (“quite unlike anything you can find on the web“) and innocuous (“None of your information is visible to anyone who couldn’t see it before the changes“). CEO Mark Zuckerberg wrote a post titled, “Calm down. Breathe. We hear you,” the uproar subsided, and today nearly all social networks resemble the news feed’s reverse chronology of status updates.

Today in Menlo Park, California, Facebook—now a public company sporting more than a billion users—unveiled the logical extension of the news feed: a search engine for the trillions of pieces of information it knows about the people who use the service. Updates don’t just come to you; they can be fetched, as well.

“Mexican restaurants in Menlo Park that my friends have been to.”

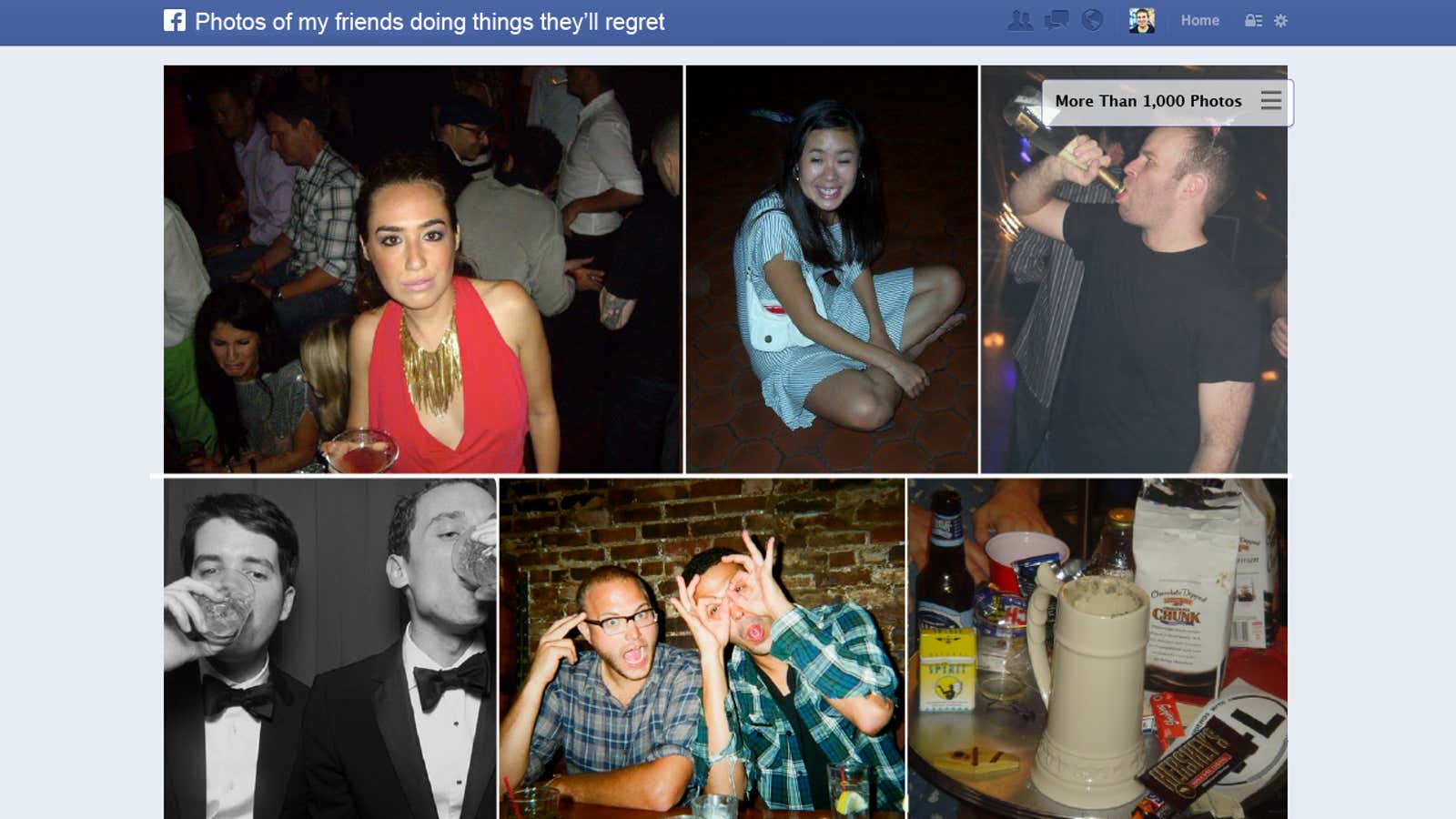

“Photos of my friends who are single.”

More than six years removed from the news feed debacle, Facebook’s rhetoric about the privacy implications of its so-called Graph Search is less defensive but similar. Zuckerberg emphasized today that users can only search for information that “your friends have shared with you” and vice versa. Once again, the new feature is being portrayed as both revolutionary and innocuous.

But in the intervening years, Facebook has taught and encouraged its users to share far more information about themselves than they were sharing back in 2006, from the places they travel to the news articles they read around the web. Zuckerberg’s Law, established in 2008, goes like this: “I would expect that next year, people will share twice as much information as they share this year, and next year, they will be sharing twice as much as they did the year before.”

In fact, Graph Search can be seen as the spoils of Facebook’s long, sometimes painful effort to move from explicit sharing (e.g., changing a favorite movie listed on your profile) to “frictionless sharing” (letting Facebook tell your friends what song you’re listening to on Spotify right now).

Though controversial, the trend seems only likely to continue. For instance, after lobbying by Netflix, the US this month amended its video privacy law to reduce the friction, so to speak, of sharing what movies you watch on social networks. And in December, Facebook updated its privacy settings to remove the ability to opt out of appearing in—yes—search results.

The combination of frictionless sharing and a search engine is powerful in all the positive ways highlighted by Facebook at its press conference today and plenty of negative ways, as well. Take one of the potential queries suggested by Zuckerberg: “Friends of friends who are single men in San Francisco.” That has been interpreted as competition for dating services, which is true, but think of it this way: a dating service you didn’t sign up for.

Or consider Instagram, the photo-sharing mobile app that Facebook acquired last year. It isn’t yet integrated with Graph Search, but that’s undoubtedly coming. Instagram is such an intimate environment for its users that many are unaware their photos are public by default. Compromising photos are already found easily on third-party Instagram search engines, but just wait until that material starts surfacing within Facebook itself.

Now, Facebook has repeatedly shown that it can get past these sorts of privacy concerns—essentially, that it knows its users better than they know themselves. Backlashes like the one that accompanied the news feed’s introduction in 2006 have always been short-lived.

As with that controversy, the reaction to Graph Search may hinge on what Facebook users feel the service is for. If they can be convinced it’s for searching a vast archive of social data—as opposed to just consuming information as it’s displayed to them—then the privacy concerns may be moot. But if searching your friends’ lives turns out to occupy an uncanny valley of social media, then Facebook may finally have pushed too far.

Last month, Randi Zuckerberg, the sister of Facebook’s founder, caused a digital kerfuffle when a photo she intended to be private ended up spreading to strangers due to privacy controls she didn’t fully understand. It was a good reminder that while Facebook may expend 10% of its computing power on privacy settings, the issue is more personal than technical. We’ll soon find out what happens when photos like Randi Zuckerberg’s start appearing in search results that we don’t anticipate, either.