hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Special report - part I] “Nut rage” shows the shortcomings of chaebol third-generation leaders

The so-called “nut rage” scandal involving Cho Hyun-ah, who recently stepped down as vice president of Korean Air, provides a disturbing look into the current state of South Korea’s chaebol. The fact that an heir to one of the chaebol - the vast conglomerates that form the core of the South Korean capitalist system - was responsible for this scandal is especially troubling and indeed alarming when one considers that control of these companies is about to be handed down to the third generation of these families.

The aberrant behavior of the scions of the chaebol can cause damage not only to the executives and employees of the company in question, but also to South Korean society as a whole. During this two-part series, the Hankyoreh will examine the irregularities in which these young heirs are implicated and will try to find a solution.

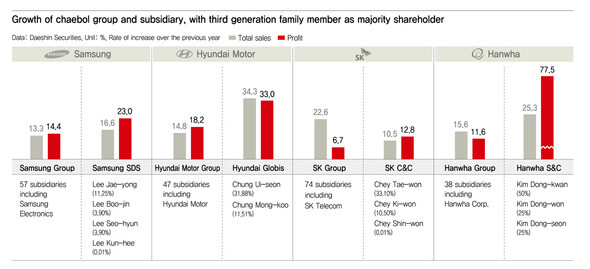

The heirs to the chaebol are already closely involved in running these companies, which constitute a substantial portion of the South Korean economy. At the Samsung Group, the largest chaebol, management rights are currently being handed down to Lee Jae-yong, Vice President of Samsung Electronics, and his two sisters. Meanwhile, the grandsons and granddaughters of the founders of other major chaebol such as Hyundai Motor, LG, Doosan, Hanwha, and Hanjin are already important executives.

The heirs to these families are largely exempt from the normal protocol for being hired and promoted. According to the Hankyoreh’s survey of 15 major chaebol, 28 members of the third generation of these families on average joined the companies at the age of 28.1 and became executives, reaching the highest run of the company, at the age of 31.2. In other words, after joining the company, it only took them an average of three years to be appointed executives.

This is absurdly short considering that it generally takes 22.1 years for a new employee fresh out of university to be promoted to the level of executive, according to a survey of 219 companies released by the Korea Employers Federation in November.

Even worse, the members of the third generation have largely accumulated the wealth that they need to inherit the management rights of these companies through expedient means such as work funneling - a practice whereby subsidiaries in a single group give large amounts of business to each other.

Cho Hyun-ah, as well as her siblings Cho Won-tae and Cho Hyun-min, are the main stockholders in Cyber Sky, an online duty-free store, and Uniconverse, an IT company, both of which are subsidiaries of the Hanjin Group. The three siblings own 100% and 85% of stock in the two companies, respectively, and internal transactions within the group accounted for 83% and 66% of the total revenues at these companies in 2013.

In addition, Lee Jae-yong and his sisters Lee Boo-jin and Lee Seo-hyun raked in trillions of won in profit when Samsung SDS and Cheil Industries (formerly Everland) - two countries whose growth had been fueled by such internal transactions - went public, earning the siblings 200 to 300 times more than their initial investment.

This pattern can be seen at nearly all of the chaebol. The dominant stockholders at IT companies such as SK C&C and Hanwha S&C and advertising agencies likes Hyundai Innocean and Lotte Daehong Communications are the heirs to the family, most of the work that these companies do comes from within the group, and their revenues and operating profits are much higher than the group average.

It is generally understood that many of these members of the third generation were not carefully vetted for their moral standing or business acumen. The issue is that their failings do not only affect themselves, but can also have serious ramifications for their companies, and indeed for South Korean society as a whole.

Korean Air spends around 50 billion won (US$45.27 million) on advertising every year, but the loss inflicted on the company’s brand image by Cho Hyun-ah’s hijinks is thought to be even greater.

When Lee Jae-yong was promoted to vice chairman of Samsung Electronics in 2011, the Economist suggested that this would not be a problem as long he has a knack for business. But if he does not, the magazine warned, South Korean society as a whole would be in for some serious trouble.

The prediction applies not only to Samsung but to all of South Korea‘s chaebol. At the Hyosung Group, the company’s brand value and management have suffered a massive blow after Chairman Cho Suck-rai was charged with using fraudulent accounting to dodge taxes and his eldest son and company president Cho Hyun-jun was charged with avoiding the gift tax by putting money in an overseas account under an assumed name.

“There is an experience gap between the hard-working founders of the companies and their children, who saw how hard they worked, and the third generation, who were born in the 1970s and 1980s. The younger generation lived in luxury from an early age, and they are less observant of their surroundings. They show a tendency to only focus on advertising and IT, areas that are flashy and easy to run,” said a high-ranking executive at one of South Korea‘s largest companies.

As the macadamia nut episode illustrates, bad behavior by chaebol families, especially the less experienced and capable third generation, is viewed widely as a time bomb just waiting to detonate for the company and the public. For this reason, many are calling for independent management successions within the companies to go alongside institutional measures to prevent abuses by the families.

Chae I-bae, an accountant for the group Solidarity for Economic Reform, said one way to increase management transparency would be to give outside board members the access to information and powers that would allow them to live up to their intended role, rather than serving as “yes-men.”

“The companies themselves also need to implement succession programs to groom future leaders who are competitive,” Chae added.

Others are calling for a more fundamental move away from the inheritance of management powers and wealth by chaebol children.

“We’re past the days when you were guaranteed a role in management and management powers just because you were the child of a chaebol family,” said Song Won-geun, a professor of industrial economics at Gyeongnam National University of Science and Technology.

“They need to adopt the same kind of system that the top companies overseas use, where the children of major shareholders get ownership but no management authority, or where the only people who get to participate in management are the ones whose abilities have been tested over the decades,” Song added.

Even many within the business community agree that a shift in attitudes from the chaebol clans is overdue.

“It’s difficult [for a company] to survive when the owning family maintains an imperial leadership system,” said LG Academy director Lee Byung-nam.

“Society has developed, and chaebol leadership needs to change too,” Lee said.

By Lee Jeong-hoon, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 4No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 5Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 6US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 7[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 8[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 9Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 10Samsung subcontractor worker commits suicide from work stress