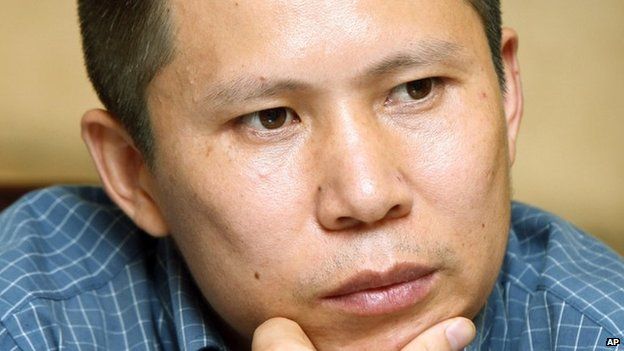

China activist lawyer Xu Zhiyong on trial

- Published

Xu Zhiyong, a prominent human rights lawyer who campaigned against corruption, has gone on trial in China.

Mr Xu is charged with "gathering crowds to disrupt public order". He is one of several activists from a transparency movement to be tried this week.

Rights groups have criticised President Xi Jinping - who pledged to fight corruption - over their trials.

They come as a report says many members of China's elite have set up offshore companies in overseas tax havens.

The trial of Xu Zhiyong, who was arrested in July 2013, began on Wednesday in Beijing.

There was tight security outside the court, with police blocking journalists from approaching or filming outside.

A BBC team reporting from a street near the court were forced to move after a group of men in plain clothes pushed the crew down the street.

BBC reporter Martin Patience is moved on by 'undercover thugs' at China trial

CNN reporter David McKenzie said on his Twitter feed that he had been "manhandled, detained, and [had] equipment broken" near the courthouse.

Western diplomats said they were able to enter the building but were not allowed into the courtroom itself.

Mr Xu's lawyer, Zhang Qingfang, told the BBC that Mr Xu and his lawyers both viewed the court proceedings as illegal, and stayed silent during the trial in protest.

Earlier, Mr Zhang told reporters that a fair trial looked "unlikely". He said that he had not been given the opportunity to defend Mr Xu in a fair court.

"Last week I applied for five witnesses to come and testify, but not only did the court reject my application, but also the police have been restricting these witnesses in the last two days," he said.

In a press briefing on Tuesday, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Hong Lei described Mr Xu's case as a "common criminal case" and that Mr Xu had been "arrested in accordance with the law".

'Hypocritical crackdown'

Mr Xu, who was also previously under house arrest, is a leading advocate of a group campaigning for government officials to reveal their wealth.

Seven members of the informal grassroots group, New Citizens Movement, also face separate trials this week on similar charges.

A known legal scholar, Mr Xu also campaigned on behalf of inmates on death row and families affected by tainted baby milk formula in 2009.

In a video message from prison last year, he urged people to unite in pursuit of democratic freedoms.

No matter how "absurd" society was, he said, "this country needs brave citizens who can stand up and hold fast to their convictions".

Mr Xu now faces up to five years in prison for disturbing public order, the BBC's Celia Hatton in Beijing reports.

Human rights advocates say Mr Xu's true crime was to go too far in pushing the ruling Communist Party to expose the illicit wealth of some government officials, our correspondent adds.

Rights group Amnesty International condemned what it called China's "hypocritical crackdown on anti-corruption campaigners".

"Instead of President Xi Jinping's promised clampdown on corruption, we are seeing a crackdown against those that want to expose it," Roseann Rife, East Asia research director, said in a statement on Tuesday.

Xu Zhiyong was a "prisoner of conscience and he should be released immediately and unconditionally", Ms Rife added.

"Anything less would make a mockery of the Chinese government's ongoing anti-corruption efforts."

'Hidden riches'

Meanwhile, a report by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) said relatives of many of China's political elite, including the brother-in-law of Mr Xi, and the son and son-in-law of former Premier Wen Jiabao, owned offshore companies in international tax havens.

It said that almost 22,000 offshore clients with addresses in mainland China and Hong Kong appear in leaked documents from two offshore firms that set up offshore companies and accounts for clients.

The practice is legal, but the revelations, if true, shine a light onto the wealth of the families of many Chinese leaders, and could embarrass members of the political elite.

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Qin Gang dismissed the allegations.

"From a reader's point of view, the logic in the article is hardly convincing," he told a regular press briefing. "That is sure to raise suspicions over the motives behind it."

The Guardian newspaper, which was part of the investigation, said that its website appeared to be partially blocked in China on Wednesday, as was the website of the ICIJ.

In October 2012, a New York Times investigation said that members of then-Premier Wen Jiabao's family had amassed "hidden riches" of billions of dollars.

Lawyers for Mr Wen's family rejected the claims, and said that while some of the family were involved in business activities none of it was illegal.

Both the New York Times' Chinese and English sites were blocked in China after the report.

- Published17 July 2013

- Published27 February 2013

- Published28 January 2013